Posted on 16th February, 2026 in Blog posts

The business of business is not just business

President Trump is fed up with the hypocrisies of the ‘international order’ which European leaders care so much about. He thinks it’s just a cover for getting the USA to serve European interests, i.e. allowing them to buy electorates by doling out welfare while the USA pays the bill for making the world safe for their evangelism. He’s not entirely wrong. But while trying to right that wrong, he has also ditched something quite remarkable in the stages of human development: the idea that we might cooperate for moral reasons, rather than just to make money.

President Trump has resuscitated the slogan often attributed to President Calvin Coolidge and used to explain why the USA should not concern itself with moral questions or political matters beyond its own sphere of influence, ‘the business of the USA is business’.

After the Second World War, the allies who had defeated the totalitarian menace recognised that they had cooperated – no one nation can be credited with victory – in the common good, including the good of the Germans and the Japanese. With the exception of Joseph Stalin, who saw the war simply as power play, the leaders had put morals before material interest. And they hoped that, with the United Nations (1945) and the EEC (1957) we could put greed behind us and cooperate. Thoughtful people had begun to realise that all civilisations had sought to identify values from nature and that altruism, though dressed up in different religious or philosophical guises, were universal. Now we needed institutions for their realisation.

The enterprise revolution

The commercial and scientific revolutions of the 17th and 18th centuries gave rise to a great many enterprises which, though usually planned to provide an income for their founders, were justified by the value of the products or services they provided. Personal benefit was justified by social contribution. The best known examples of this in the UK are Cadbury and Boots, in which making and selling a good product was the basis for a flourishing life for communities of employees, subcontractors and, ultimately, a great deal of philanthropy too. The business of those businesses was much more than business.

And today, there is all the more reason to say that no enterprise of any size is the absolute property of one person, especially not of the one who provides the money, if he is not the investor in time or ideas.

Every enterprise, old and new, depends on a hinterland of stakeholders for its survival and success. These include the institutions that educated the founders, the community that provided the employees, the local authority that made available resources, and the nation whose infrastructure of laws and administration made it all possible. The idea that, when a company’s future is being considered, the only people with skin in the game are financial investors, is anti-social. Alex Brummer wrote a whole book (Britain for Sale) excoriating the way in which big shareholders flog off companies to predators regardless of any other stakeholders.

Claims made in times of crisis that ‘we are all in it together’ ring hollow when the pursuit of individual ambition and personal profit have been exalted as the very purposes of life. Paul Collier argues that we must get away from the reductionism implied in the expression ‘economic man’.[1] He advances the truism of ‘social man’, emphasising reciprocity. I will add to that: Once the initiators of businesses have made enough to keep themselves and their families well, it is not the purpose of a business to make individuals filthy rich. Profit is a discipline, not a purpose. The purpose of an enterprise is the contribution of its particular inventions, product or service to society and the community.

Collier also advocates heavy taxes on asset management and on those who live off rents rather than enterprise, to nudge the highly skilled towards socially valuable investments.[2]

Colin Mayer not only wants companies to enshrine a higher purpose in their mission statements, but also applauds the foundations that oversee companies such as Tata, Bosch, Ikea and Carlsberg, guaranteeing stable ownership, board accountability and social purpose.[3] He wants to save capitalism from the revulsion felt by many at the global tax arbitrage, executive pay balloons, selfishness and short-termism of some corporations.

An old fashioned rural enterprise

I was putting flowers on my aunt’s grave when the revelation suddenly came to me. My aunt is buried in the roofless chapel on an estate in Fife, her home for over 70 years. Once I had laid the flowers on the tomb I started to glance around at the other memorials and tombstones. That day, I saw them in a new light. This particular estate has been in the hands of one family for over 800 years. Yet many of the memorials do not memorize members of that family. There are names of those of relatives, some of whom had never lived in the big house, but associated themselves with it. Others were dependents: church ministers, cooks, gamekeepers, foresters, farmers, ploughmen and carpenters. I suddenly realized something which I had never thought much about before: the estate is not just to do with one family – even of all the family members who are living, those who are dead and those who are to be born – but a community. I had been kind of aware of this when I visited my cousin John in Ireland, who told me that when he inherited his estate in the 1960s, there were a great many dependents. Before he could rationalize and modernize his inheritance, there were aunts and uncles who had to be provided with their portions, retired estate workers who had to be confirmed in their homes. And even after he had done that, he always welcomed to the big house those who had some connection with the estate, even tenuous.

Is this so different, except in scale, from Cadbury’s, Rowntrees, Unilever, a school or a high-tech company today?

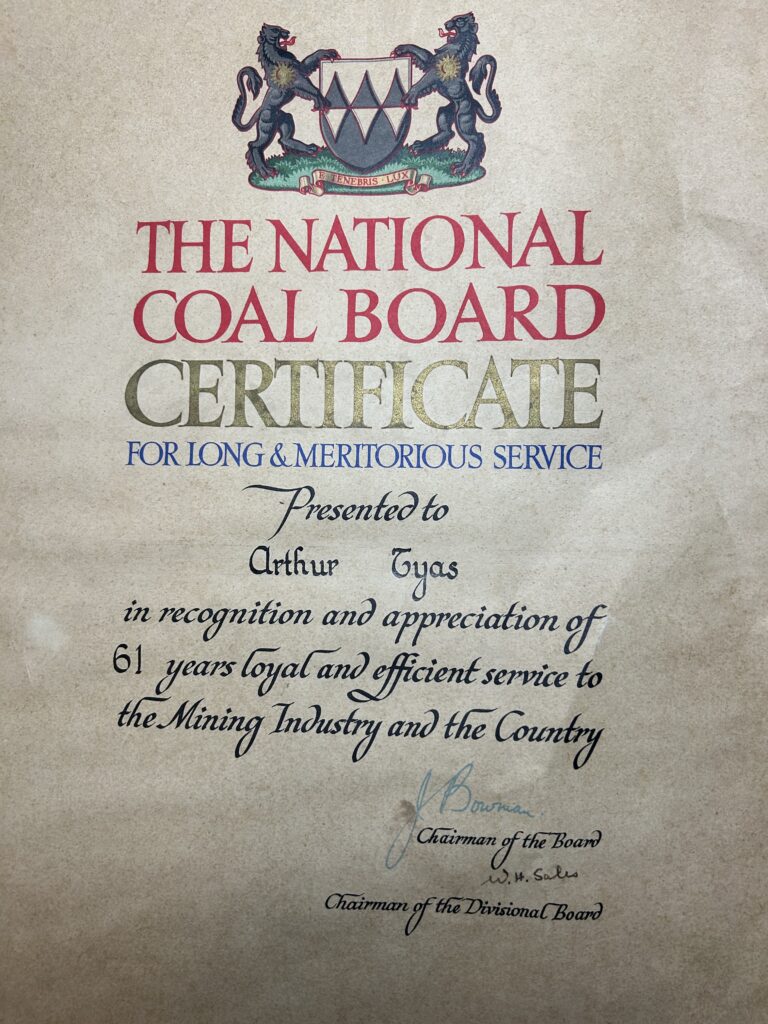

A few days later I was back in London nosing around a junk stall in the East Street Market when I came across a certificate awarded to a miner for 61 years’ service. This reminded me of the miners’ gala which I used to enjoy when they convened, with pipes and drums, on Holyrood Park in Edinburgh, a short walk from the home of my youth. Like that miner whose name is on the certificate, much if not all his identity was bound up with the industry and the company in which he worked.

A community of people coheres around an idea, a shared vision, simple – we’ll make the best doughnuts – or complex – our application of AI will provide predictive diagnostics and save many lives. There are people with ideas, people with money, people with energy and people with skills. A product, and a world, is created. The business of business is not just business.

[1] Collier, Paul (2018) The Future of Capitalism: Facing the New Anxieties London: Allen Lane

[2] Collier, ibid, p187

[3] Mayer, Colin (2018) Prosperity Oxford: OUP, pp161-163