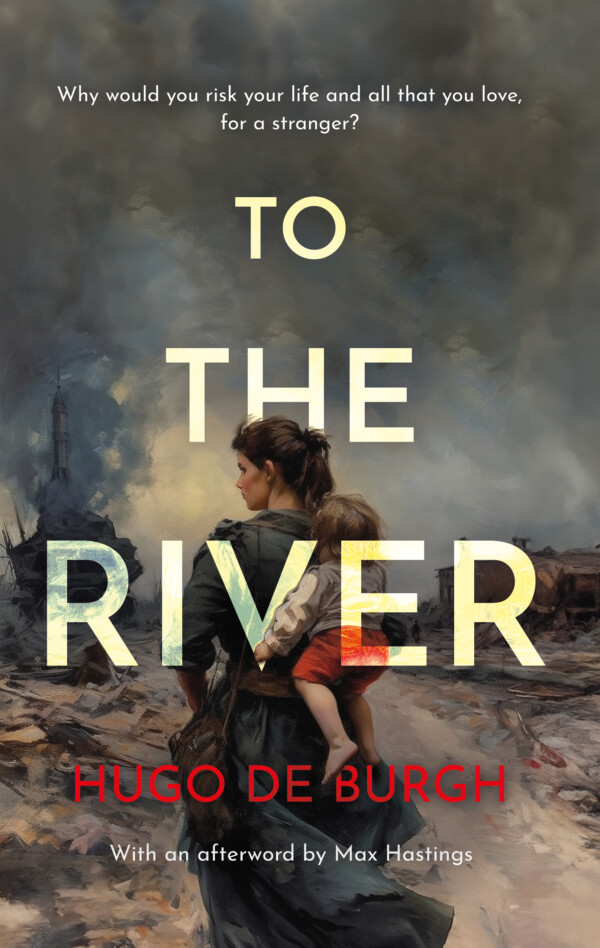

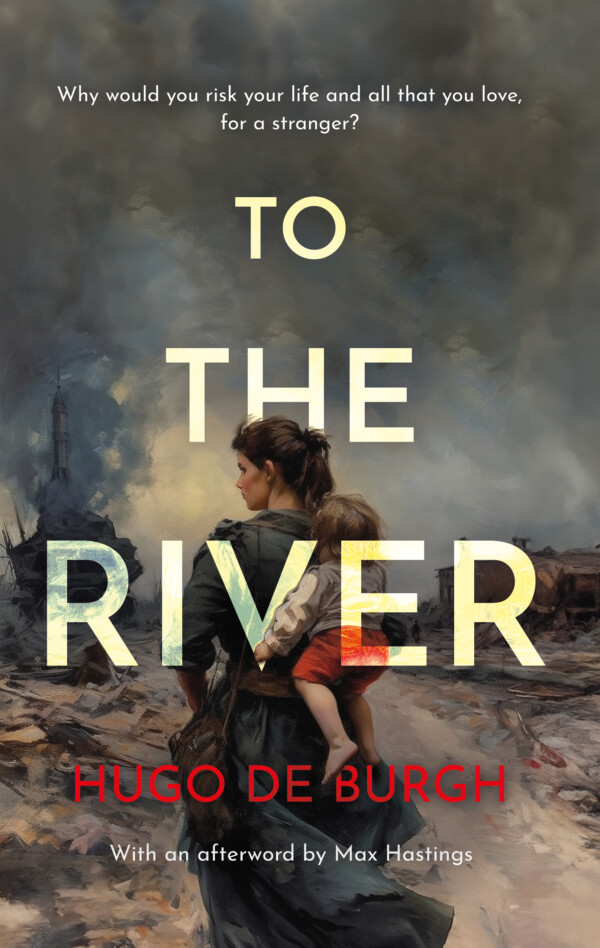

With an afterword by Max Hastings. Launched at the Mansion House, London, in November 2024.

To The River

Why would you risk your life and all that you love, for a stranger?

Umbria 1943.

Nazi troops are massacring whole villages in retaliation for help being given to even a single fugitive.

Outside a pretty country town is a prison camp of six hundred British, Commonwealth and American soldiers seething with hatred for Italians. When young widow Lucia does a deal with FitzGerald, all six hundred escape into the hills or make their way out of Nazi occupied Italy. FitzGerald himself moves from farm to farm until his contempt for Italians turns into admiration for the impoverished people who risk everything to succour a stranger. He sees in the women, children and old people left on the farms, a courage greater than that of soldiers. Instead of taking up arms again, he shepherds the villagers as they fly from extermination.

But can he and his rescuer escape To the River, the border between two armies?

Paperback ISBN: 9781805142485 • £9.99

Profits from the sale of this novel will go to the Monte San Martino Trust, charity no. 1113897

Origins: How To The River got made

Mrs Riva and the nine year old I were walking in the forest around Gavinana when we found a helmet. As I brushed off the earth, Mrs Riva explained about the escapees who had been hiding there in 1943-4, and how she had taken them food. In time I would meet many surviving rescuers, like Mrs Riva.

We stayed with Mrs Riva because my mother, after the death of my father (PTSD) when I was aged 4, had sought teaching jobs abroad. By my 7th birthday we were in Italy and the circles in which we moved consisted of people with whom my mother had worked in the last years of the Second World War.

A very young intelligence officer, her first posting, in 1941, had been to Latimer House where, as a member of Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Centre (CSDIC), she worked with German and Italian colleagues in investigation and observation of captured enemy generals. She specialised in the collection of data about atrocities. Thence, she had been sent to North Africa and, when we invaded Italy, to Allied HQ at Caserta, near Naples. In 1945 she transferred to the Allied Screening Commission (ASC) because it was ‘more about people than maps’. My father had been appointed commanding officer of the ASC in 1945 and the 26 year old, who by that time was fluent in German, Italian and French, became his intelligence officer. The ASC investigated the fate of allied agents and escaped prisoners, making copious records of how they had been treated; from their researches emerged the story of what a historian, writing in the 1970s, called ‘the Strange Alliance’.

In 1956, my mother took a post teaching in Rome. The friends she looked up were all people with whom she had been involved in her work for the Allied Screening Commission, usually people who had defied the cruelty of the Nazis to help fugitives and refugees, those of the ‘Strange Alliance’ of rescuers and outlaws. I just took them and their discussions about the war for granted. My best friend at school came from the other side; his mother had been an officer in the fascist youth movement for girls, his father a professor of economics.

While in the army of occupation, my mother had also had dealings with Italian government and had become friends with a lady who had worked as a Secretary to the Minister of Marine during WW2, who was her uncle. I suppose that they were professionals, rather than fascists. This lady’s nephew, a physician and psychiatrist, married the niece of the 14th Count of Le Pastene, who held Ministerial and other portfolios under Mussolini. In later life I came to know the physician’s family very well indeed, and their friends, whose fathers had often had senior positions in the bureaucracy or military before 1944.

It was not until the 1980s that I started to take an interest in my parents’ wartime experiences, to learn the British side of the story. It was as a result of receiving, in 1982, a letter from an Anthony Laing, inviting me to join an ‘Annual Fontanellato Lunch’ in London’s Haymarket, which I did. In consequence, over the 1980s I met many of those who, with my father, had broken out of Fontanellato Camp in September 1943. My first hosts at the Fontanellato Lunches were Anthony Laing, Ian English, Peter Langrishe and Maurice Goddard.

Another was Stuart Hood, who had been my father’s ADC in the camp, then a partisan in the hills. After WW2, Stuart Hood was the Controller of BBC Television, prolific author and a Professor at the RCA. Through him I met, read memoirs of, or corresponded with, other former fugitives. Tom Craig and Reg Wheeler wrote me eulogies of my father which told me that they attributed their survival to his leadership; he had been their hero. I talked about these events with my mother for the first time; when, in the late 1990s, my son found the manuscript of a book she had written about her wartime experiences, we got it published as My Italian Adventures: An English Girl at War 1943-47 (Lucy de Burgh; available from Amazon, as elsewhere).

Finally, when the Covid crisis shut us all in our homes and my work with Chinese creatives and students evaporated, I decided that I wanted to give new life to the tales from those times and to draw attention to the lessons the fugitives had learnt.

Who wrote this novel?

To the River is not so much written by me as compiled by me. The authors are all dead. I have tried to bring them back to life.

The whole intention of this book is to give new life to other people’s memories, to retell their stories in an idiom which may attract new generations. So, in several places I have, with permission, deployed the words of Uys Krige’s The Way Out, Stuart Hood’s Carlino (also: Pebbles from my skull) and Eric Newby’s Love and War in the Apennines, all fine writers whom I could never emulate. Most of the flight over the Morrone mountains is pretty much by Uys Krige. The grape harvest is as described by Stuart Hood. The story of the butterfly collector is taken from Newby, as is that of the doctor and his car. Several conversations are verbatim; conversations like these do not take place anymore, cannot even be imagined anymore; first TV, then Social Media, have seen to that.

I thank the heirs to the writers’ estates, Brenda Heinrich (Krige: The Way Out), Svetlana Hood (Hood: Carlino) and Sonia Ashmore, as well as Harper Collins, (Newby: Love and War in the Apennines).

After Anthony Laing and his friends had befriended me, in the 1980s, in order to tell me of their respect and affection of the fellow prisoner who led them out of captivity, I met with, or corresponded with, several others, including Keith Killby, founder of the Monte San Martino Trust, which, in time, subsumed the Fontanellato lunches.

I also read memoirs and histories of the period, listed below.

Those who helped me by reading and commenting on the various drafts: Sally Usher, Mary Hodge, Alja Kranjec, Rob Benfield, Andrew Willie, Flora Rees, Susannah Okret. Thomas Krapf advised me to cut out most of the German I had incorporated. I am grateful to them all but assure them that none have any responsibility for deficiencies that remain. The publisher, Troubador, was most efficient and its staff could not have been more helpful.

What they wanted me to know

Encountering attitudes to life that challenge his own assumptions, the soldier protagonist FitzGerald faces questions that had never occurred to him before: Why do some people risk themselves and all that they love, to save strangers? What made the butcher and what the altruist? When is it that women’s leadership trumps men’s? Is the difference between male and female important to maintain? Does religion play a part? Why do so many of us put our faith in what ruins us? What is civilisation? Why is humaneness instinctive to some, but incomprehensible to others?

These themes came together as I ruminated on the part played by those Italians who took such risks in helping the hungry men flying from German captivity. That they did so was surely due to my encounter, in Arcata, California, with Samuel Oliner, an American psychologist. It was when he told me of his discoveries about virtue that I realised that what he had found from academic research had been grasped by the men who escaped from prison, and that I had met some rescuers, of the kind whom Oliner analysed, as they were our friends. When a child, Oliner had been saved by a gentile family when his parents and their entire community had been exterminated by the Germans. His story is told in a short book, Restless Memories. In later life, Oliner became a psychologist and studied rescuers, those very few people who had saved Jews slated for death. He identified a common factor which people of every generation, social circumstance and age, shared. That is the factor to which the fugitives in Italy alluded, and which I have tried to illustrate in To the River.

Professor Oliner also helped me understand why our Italian friends and many of the fugitives they helped, believed that to possess much more than what you need for immediate survival, is, in a suffering world, something of which to be ashamed. As outlaws in Italy, they had seen people reduced to nothing but their moral compass, who had lost every possession, yet were much more admirable than those who ruled over them. That was in 1943-5, when Italy was a devastated battlefield. What mattered, in those times, about people, was their quota of love for others: wealth, race, social status, occupation had no significance.

My life choices, I now realise, were profoundly influenced by these attitudes, absorbed unwittingly. After graduating, I worked in China during later part of the Cultural Revolution, then spent my earnings in Paris as a postgraduate student. After throwing up a fun life there, I was employed in community work (for the Scottish Council of Voluntary Service) in impoverished areas of Scotland. Activism led me to journalism and television broadcasting, focussing on the environment, undereducation and employability, and then to teaching journalism and trying to understand China through its media. In working with Chinese people, I began to understand the humane messages of Chinese philosophers that I had first learnt about when attending the lectures of AC Graham and DC Lau as an undergraduate, and to connect them with the values of my mother’s Italian friends.

What is real and what is imagined?

Since it sounds so fantastic that 600 men could escape together under the eyes of Hitler’s elite unit, it needs to be said that the breakout did actually happen, pretty much as described in To the River.

As to the rest, the events and characters are all based upon real people and real experiences, but they have been reworked to fit them into a narrative of composite characters.

In a few cases of minor characters, I have retained the names of the originals or something very similar. Vicedomini (Vicere in the novel) was the name of the Camp Commandant of the only camp from which all the prisoners evaded Nazi seizure, but that camp was not called PG500 Ginestra. SS officers Priebke and Reder were as real as Generals Rommel and Kesselring. However, the Bavarian Joachim Peiper, the actual commander of the Waffen SS Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler Panzer Squadron which was, indeed, based in Umbria in 1943, is disguised as Fröhlich, allowing me to adapt his career somewhat, though not his character. I made Fröhlich attend Westminster School. In fact, it was Rudolf von Ribbentrop, later also an SS officer, who was at Westminster. There were quite a few children of the Nazi cabal in the UK before 1939. Walter Darré, SS leader and head of the Reich’s Race and Resettlement Office, had attended King’s College School in Wimbledon. The SBO at Fontanellato (my father), fortunately for him, never met Fröhlich (Peiper).

FitzGerald’s story is woven from those of at least 3 men. The activities of the original senior prisoner at PG49, Fontanellato, whence the 600 escaped, are as described by former inmates Flowerdew, Wheeler and Craig. The original ‘FitzGerald’ was indeed an Irishman born in the USA. However, he did not go south but made rapid strides across the Monte Rosa to Switzerland. Thus after evacuation from PG500, all connection between the real senior prisoner and my novel’s FitzGerald ceases, and I draw upon the careers of others.

Gordon Lett managed partisans in Rossano, about which he wrote a fine book. John de Burgh, of the Ayrshire Yeomanry, wounded at Monte Cassino, told me of his passion for a young Italian girl who had been a rescuer, and was subsequently murdered. Some other experiences attributed to FitzGerald are those of Uys Krige or Eric Newby. Michael de Burgh, 9th Lancers, blown out of his tank in the last days of the war, was cared for by an Italian doctor of great skill, kindness and erudition, to whom I have given the name of a similarly endowed and dear (ex-military) doctor I knew, the Sicilian Tommaso Sciplino. Here I want to acknowledge that it was the generosity and empathy of the real Dr Sciplino that opened my eyes to many aspects of Italian life and culture and helped me to look at the Anglophone world from perspectives both Mediterranean and Asian.

Lucia is based on 3 women; her character is that of Luisa Fiore, who looked after me when I was a child. Lucia’s exploits have something in common with Renata Faccincani della Torre who was the most striking and youngest of the females who risked all to help fugitives. Unlike the other rescuer women I met in my childhood, Faccincani was a Milanese, from an eminent family. She operated safe houses for couriers, agents and anyone who needed shelter. Anti-Nazi German officers also were involved. When she lived in London in the 1960s she was a teacher of Italian who shared with my mother a love of Italian literature.

For the American Donna Chiara and her Italian husband, I have drawn upon the lives of Iris Origo, Marchesa di Cortenuova and chatelaine of Val d’Orcia, and of Contessa Blasi Foglietti, who hid fugitive Brits and whose husband joined a British army unit. Their son married my mother’s pupil, Sally Hood.

The Italian surnames are all those of families I knew as a child, though my memories of the detail of their wartime activities are hazy. They may be accessible from the files of the Allied Screening Commission, for which not only my parents, but many others, including the writer Eric Newby, worked. They are now held in the USA. The MSMT has a project to digitise them so that they may be available elsewhere.

The real Dottoressa Foschini, whom I knew as a boy, had indeed been a Leader of the Young Fascist Girls, though not in a place called Ginestra. Her son, Alessandro, was my closest childhood friend, and I have given his name to a character (of his parents’ generation) whom he resembled, though, as far as I know, the only Italian to report on what the Germans were doing in the East was the journalist Curzio Malaparte. Sandro died young, following a career as a civil servant. His daughter rents out pretty apartments to tourists in Rome, https://abnb.me/n2wdXlHmPqb, or contact direct at [email protected].

Gino, a carter, lived in the slums of Rome and would, every Sunday morning before three a.m., lay out his junk in Porta Portese market. He regaled this foreign boy with stories of resistance while selling me fascist era memorabilia that he had scavenged from the cantine (cellars) of former gerarche (fascist officials). The actual Aldo was the leader of a gang of scugnizzi (urchins) with whom I fought mock wars on the streets of Trastevere in the company of two German boys, Janni and Bushi, accoutred in the military equipment that could be found on every rubbish dump at that time. Their parents had thrown away their German uniforms in Milan 1945 and reinvented themselves as Dutch refugees in Rome, where they would remain, working in the film industry, until death a few years ago.

Dr Behrens was our dentist in Rome. He had been hidden by Italian gentiles throughout the occupation.

There were many stories of orphans discovered in ruined towns and villages. Vito’s history is based on that of Denise, picked up in Normandy in 1944 by some American soldiers from a ruined farmhouse. Seeing Yselle Simmonot, my mother’s childhood friend, by the roadside, they stopped their tank and made her take the baby. When, in 2003, I went to Normandy to look after my mother who had suffered a stroke while visiting Yselle, Denise, now with her own husband, was still living with her saviour, both thoroughly integrated into Yselle’s family.

The doctor driving scene, p180, comes entirely from Newby although I have located it further south. In fact, Newby was taken to, and was to be hidden in, Soragna Castle. In 2018 I visited the Meli Lupi Prince of Soragna in his magnificent castle and, as he told me of his parents’ hiding of British fugitives, was amused to see a photograph of his father in Fascist uniform and, in a display case, the pugnale, or dagger, of an officer of the blackshirt militia.

The negative presentation of the Vacca landlords is not meant to condemn all the Italian nobility. Aside from the Soragna, there were among the landowners many who helped fugitives at great risk and were active in the anti-fascist cause. The name Malvezza dei’ Medici crops up regularly in the ASC correspondence. The most prominent was Prince Doria Pamphili, the first post-fascist mayor of Rome. His daughter and my mother set up the first Save the Children Fund branch in Rome in the 1960s, in an attempt to tackle destitution and suffering in southern Italy, as grievous as that in India. Child beggars and the intentionally mutilated were a common sight of my childhood in Rome.

Priests

The role of the priest from Friuli is invented, though not the type. Catholic priests in the Balkans supported and in some cases themselves carried out, repression of non-Catholics. The escape of some of the most disgusting of the Nazi war criminals (including Priebke) was aided by a Catholic bishop, Hudal. On the other hand, the Vatican condemned those Croat priests and, notwithstanding the charges made against Pius XII by Rolf Hochnuth, exhorted religious to give succour to Jews and other refugees during the persecutions. Thousands of lives were saved thanks to that.

The ambiguity of the religious in To the River perhaps warrants explanation: I wanted to point to the equivocal relationship of religious faith to virtue and, to realise in my story the findings of Samuel Oliner, mentioned above.

As a boy living in Rome in the late 1950s and early 1960s, I saw the then Popes, Pius XII and John XXIII, being carried in a palanquin and surrounded by, interalia, the Noble Guard. I recollect seeing the announcement Habemus Papem from the balcony; my mother and I must have queued for hours; she was not a Catholic but loved theatre. These must have been almost the last times that the papacy presented itself not only as a spiritual power but as a temporal one, with all the trappings of a monarchy, deriving its rituals from ancient Rome.

Father Wolfgang is based on the Bavarian Martin Krapf, beloved ‘uncle’ and father of my most longstanding friends. He deserted the German army in France in 1944, at the first opportunity. Imprisoned in England, he later, after studying theology at Cambridge, became a Lutheran Pastor and married a refugee from Berlin. He took me to see a film, der Hauptmann von Köpenick, which satirises the respect for, and love of, uniforms, and their influence on wearers and observers alike.

Monsignor O’Flaherty was a hero. There are books and films about his exploits.

Facts

After 1945 the Allied Screening Commission found that, of over 80,000 Allied prisoners in Italy, more than 50,000 had been obliged to obey the Stay Put Order and been transported to the Third Reich, often as slave labour. Many died in German captivity. There was only one camp in which the Senior Prisoner disobeyed the Stay Put Order and all prisoners got out, PG 49 Fontanellato.

In Italy, help to the hunted, whether Jews, deserters, politicals or escapees, was much more common than turning them in, to the authorities. Some thousands of Italians were murdered for giving succour to fugitives, a small proportion of the great numbers of Italians shot or burnt alive simply because they were inconvenient to the German army. Nevertheless, a greater proportion of fugitives were saved in Italy than in any other occupied country.

Over 700,000 Italians were transported to Germany or its East European colonies as slave labour. Mussolini tried, and failed, to get them released. Very many died of maltreatment by German business managers and foremen. Survivors received no compensation or apology.

As at 2021, many of the villages destroyed by the Germans have never been rebuilt as the entire communities were annihilated. Germany paid no reparations.

Of the German soldiers who had ordered or carried out massacres only one was executed, a few spent short terms in prison, all (including the SS) received excellent state pensions for the rest of their lives and most were provided with good jobs by German industry or took up important posts in the political institutions of post war Germany. Those who, like Priebke, used the escape line of Bishop Hudal, mainly went to Latin America.

Timeline

Experts on the Italian campaign and civil war will note that, though all significant events mentioned in To the River did take place, I have sequenced events to suit my story.

I have described a German retreat northwards in Autumn 1943; the main retreat took place in August 1944.

The rounding up of Jews in Italy, by the Germans and their fascist assistants, generally started in September 1943, not the month before. Although 1st Panzer (and therefore its commanding officer) was in Italy in 1943, it actually left Italy earlier than I have allowed. The meeting between that commander and the two German policemen may never have taken place, although plausible. Café Rosati was the favourite resting place for the SS leaders as it was, after their departure, for the British. It is still a fine café.

On his return from Ukraine, I have Foschini reporting to Salò before the Italian Social Republic (RSI) was actually set up. I place Marshall Graziani and Minister Gentile there in advance of the rescue of Mussolini.

Some of the events referred to took place after the date ascribed here (eg the Cephalonia massacres, the SOE drops); this is because I wished to retain the brevity of Uys Krige’s experience while reminding readers of the context enjoyed by Stuart Hood and others who remained behind the lines, well into 1944.

The list of massacres is more or less that cited by Krige. They all took place as described, but not necessarily in 1943. For a list of atrocities in 1943 (i.e. during Rommel’s command) see http://www.straginazifasciste.it/?page_id=776

The only invented events are:

- The finding of the plans. Of the escapees from ‘Ginestra’, there were those who stayed put among the peasants, for whatever reason, those who went north, east or even west, and those who went directly through the lines to the south. I wanted FitzGerald to delay, but then I had to find a reason for him to up sticks and complete his original intention.

- The arrival of the Red Cross column at the Hermitage. German medical services commandeered premises regularly but the Hermitage was not so commandeered, being too far from the main lines of retreat. I needed to get Lucia and FitzGerald out of their safe house quickly.

I am open to criticism for my mistakes and thieving. But if I have realised the experiences and emotions of the men and women whose stories I seek to tell, I will be content.

I had thought, seeing how bitter is that wind

That shakes the shutter, to have brought to mind

Those that manhood tried, or childhood loved

Or boyish intellect approved,

With some appropriate commentary on each;

Until imagination brought

A fitter welcome; but a thought

Of that late death took all my heart for speech.

WB Yeats: In Memory of Major Robert Gregory

Books on this period

Absalom, Roger (1991) A Strange Alliance, Florence: Leo S Olschki

Alexander, J.L., (2013) On Getting Through, Attraversando Le Linee. Civitella Roveto: ACE Graphic Solutions.

Billany, Dan., (1986) The Trap. London: Faber and Faber Limited.

Brown, Harry., (1944) A Walk in the Sun. London: Martin Secker & Warburg Ltd.

Carver, Tom., (2010) Where the Hell Have You Been? London: Short Books.

Corbino, Eugenia (2012) Il bene e un capitale, il male e un debito. Dottorato di ricercara in XX Secolo: Politica, Economia, Istituzioni, Universita degli Studi di Firenze, Cicclo XXV

Davies, Tony., (1974) When the Moon Rises. Great Britain: Futura Publications Limited.

Duggan, Christopher., (2013) Fascist Voices: An Intimate History of Mussolini’s Italy. London: Penguin Random House.

Duke, Vic., (2011) Another Bloody Mountain: Prisoner of War and Escape in Italy 1943. London: Iron City Publications.

Ellis, Ray., (2014) Once A Hussar: A Memoir of Battle, Capture, and Escape in World War II. New York: Skyhorse Publishing.

English, Ian., (1994) Assisted Passage: Walking to Freedom, Italy 1943. London: Naval & Military Press.

English, Ian., (1997) Home by Christmas? England: The Cromwell Press.

Forman, Denis., (1991) To Reason Why. London: André Deutsch Limited.

Fry, Helen., (2021) MI 9: A History of the Secret Service for Escape and Evasion in World War Two. London: Yale University Press.

Graham, Dominick., (2000) The Escapes and Evasions of ‘An Obstinate Bastard’. York: Wilton

Holland, James., (2009) Italy’s Sorrow: A Year of War 1944–45. London: Harper Press.

Hood, Stuart., (1973) Pebbles from My Skull. London: Quartet Books Limited.

Hood, Stuart., (1985) Carlino. Manchester: Carcanet Press.

Jones, Donald I., (1980) Escape from Sulmona. New York: Vintage Press.

Kindersley, Philip., (1983) For You the War is Over. Kent: Midas Books.

Krige, Uys., (1946) The Way Out. Cape Town: Unie-Volkspers, Beperk.

Lamb, Richard., (1993) War in Italy: 1943-1945. London: John Murray Ltd.

Lehndorff, Count Hans Von., (1963) East Prussian Diary, A journal of Faith 1945-1947. London: Oswald Wolff Limited.

Lett, Gordon., (1955) Rossano (An Adventure of the Italian Resistance). London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Lewis, Norman., (2002) Naples’s 44: An Intelligence Officer in the Italian Labyrinth. London: Eland Publishing Limited.

Lindsay, Franklin., (1993) Beacons in the Night: With the OSS and Tito’s Partisans in Wartime Yugoslavia. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Marinucci, Rosalba Borri., (2009) E Si Divisero IL Pane Che Non C’era. Barcelona: Qualevita.

Minardi, Marco., (2020) Bugle Call to Freedom: The PoW Escape from Camp PG 49 Fontanellato 1943. London: Monte San Martino Trust.

Moorehead, Caroline., (2019) A House in the Mountains: the Women who Liberated Italy From Fascism. London: Chatto & Windus.

Newby, Eric., (2010) Love and War in the Apennines. London: Harper Press.

Origo, Iris., (1947) War in Val D’Orcia. London: Jonathan Cape.

Ranfurly, Hermione., (1994) To War with Whitaker: Wartime Diaries of the Countess of Ranfurly, 1939-1945. London: Mandarin.

Scott, Arch., (1985) Dark of the Moon. London: Cresset Books.

Seogo, Edward., (1945) With the Allied Armies in Italy. London: Collins.

Stafford, David., (2011) Mission Accomplished: SOE and Italy 1943-1945. London: The Bodley Head.

Sullivan, Mark., (2017) Beneath A Scarlet Sky. Seattle: Lake Union Publishing.

Tudor, Malcolm., (2000) British Prisoners of War in Italy: Paths to Freedom. Powys: Emilia Publishing.

Tudor, Malcolm., (2016). Among the Italian Partisans: the Allied Contribution to the Resistance. London: Fonthill Media Ltd.

Unwin, Frank., (2018) Escaping Has Ceased to Be a Sport: A Soldier’s Memoir of Captivity and Escape in Italy and Germany. South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military.